It’s amazing how one can be born and grow up somewhere and never learn about some of the most important places or events in its history until adulthood or old age. The schools simply failed to teach those things, and parents never thought of doing so.

As I’ve mentioned in earlier posts, I was born and grew up in Knoxville, Tennessee, but never was taught that a major Civil War battle occurred there. I learned of the event only after reaching college. At the time of the war, the Battle of Knoxville (or Fort Sanders) was considered on the par with the Battle of Gettysburg in military importance. But I grew up thinking every time I heard the words Fort Sanders only of Fort Sanders Presbyterian Hospital, which was located on the site where the bastion stood.

Then, while on a trip to the Southwest, I made a serendipitous stop at the U.S. Cavalry Museum at Fort Reno, Oklahoma, where I learned that German and Italian POWs were incarcerated during World War II. My subsequent research into similar POW camps led to my discovery of Camp Crossville, a POW camp that had existed in Crossville, Tennessee, just west of Knoxville.

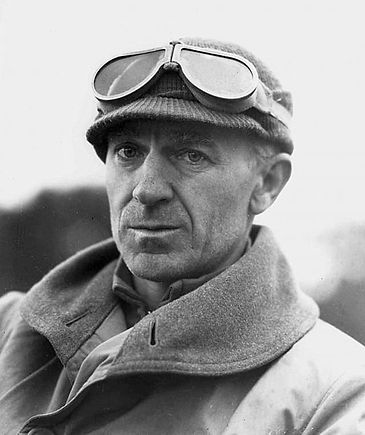

My latest discovery was Camp Tyson, which was located farther west of Knoxville near Paris, Tennessee, and named for Brigadier General Lawrence Tyson, a prominent Knoxvillian who served during World War I. (Knoxville’s McGhee Tyson Airport and the adjacent McGhee Tyson Air Force Base, home of the 134th Air Refueling Wing, are also named for him.)

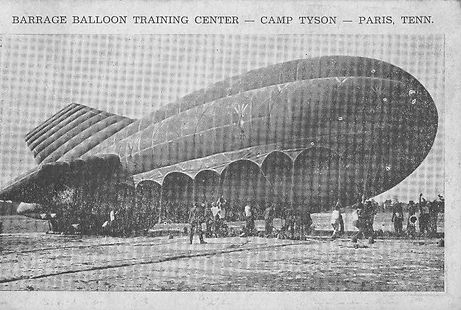

Camp Tyson was the only World War II barrage balloon training center in the United States. There, soldiers were taught to build, fly, and repair large (35 ft. diam., 85 ft. long) helium- or hydrogen-filled balloons for use in aerial defense. (See training session in progress in the photo to the right.) The 2,000-acre camp boasted 450 buildings and trained approximately 20,000 to 25,000 soldiers during the course of the war. It was a staging area for soldiers who were deployed throughout the various theaters of the war. It also was used as a POW camp.

The barrage balloons were made of two-ply cotton fabric impregnated with synthetic rubber. They cost between $5,000 and $10,000 each. The soldiers gave them various nicknames, including “air whales,” “big bags,” and “sky elephants.” Enemy bomber and fighter pilots called them trouble. (See balloon being launched in photo to the left.)

The balloons were suspended 9,000 to 12,000 feet in the air and tethered by steel cables near important buildings, bridges, ships, and other vulnerable structures to deter low-flying enemy planes. Sometimes explosives were attached to the cables to further discourage enemy planes from coming close to the structures the balloons were protecting.

The buildings at Camp Tyson included not only barracks for 535 officers and more than 8,000 enlisted men but also a 400-bed hospital, a 2,500-seat theater, a post office, a service club, two chapels, a library, a hydrogen-generation plant, an incinerator, a balloon hangar, a motor pool building, and a sewage treatment plant. It also had ten miles of asphalt-covered roads and five miles of railroad tracks. The camp even had its own newspaper called, appropriately, The Gas Bag.

When the soldiers completed their training at Camp Tyson, they were deployed to places in the various theaters of war to provide antiaircraft duty, including flying the balloons, repairing damaged balloons, helping with antiaircraft artillery, and manning searchlights. (The photo to the left shows barrage balloons protecting the invasion fleet off the beaches of Normandy.)

Now why weren’t we Tennessee boys and girls taught about this important base when we were in school? Perhaps it was overshadowed by the more earth-shattering story of what took place closer to home in Oak Ridge, where the first atomic bombs were fabricated. Nonetheless, it’s such serendipitous discoveries that make history a never-ending supply of interesting research material.

What similarly serendipitous discoveries have you made about your hometown or state?