During the process of researching and writing my upcoming book Dillon’s War, I repeatedly found myself encountering quotations from or references to various war correspondents. Many of those people reported the events of the war from the front lines or very near those scenes of combat. Some of them were wounded or killed as a result of such close-in reporting. I’d like in this post to highlight a few of them. Some of them you might have heard of; others might be unknown to you–until now.

I’ll start with Don Whitehead because I grew up reading a column he wrote for the Knoxville News-Sentinel, my hometown paper. Don was born in Inman, Virginia, only about 40 miles from the Tennessee state line.

During World War II, Whitehead was a war correspondent for the Associated Press, first covering the 8th Army in Egypt and the U. S. Army in Algeria. He later covered so many Allied invasion campaigns that he was known among his fellow correspondents as “Beachhead Don.” Those campaigns included the invasions of Sicily and of Italy at Salerno and Anzio, the D-day invasion of Normandy, the breakout from the bocage in Operation COBRA, the pursuit of the German army across Northern France, the liberation of Paris, the crossing of the Rhine with the First Army, and the meeting of U. S. and Russian troops at the Elbe River.

Whitehead wrote six books, including The FBI Story, which I read as a kid. He also wrote his column titled Don Whitehead Reports covering a wide variety of random subjects. I especially recall his column “On Where Time Goes” and a tongue-in-cheek selection about “Most Doctors and His Recommendations.” He was the winner of two Pulitzer Prizes and the Medal of Freedom.

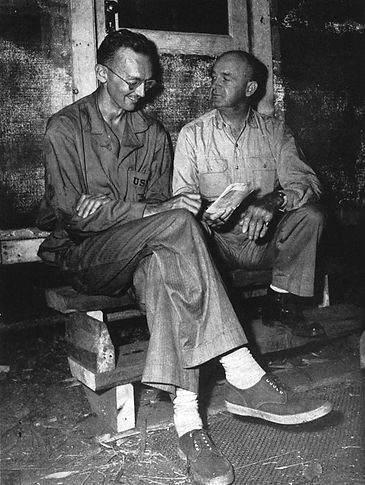

Another war correspondent with whom I became familiar as a kid was Richard Tregaskis, who reported for the International News Service. (He is on the left in the photo with Marine General Vandegrift.) My introduction to Tregaskis was through the most famous of his more than a dozen books, Guadalcanal Diary. In it, he reported on the combat of the U. S. Marines during the first seven weeks of the six-month Battle of Guadalcanal. So well written is that book that the U.S. military still lists it as essential reading for its officer candidates.

Tregaskis later covered the war in Europe, including the invasions of Sicily and Italy. From those experiences, he wrote Invasion Diary. He lived right with the soldiers who were doing the fighting. So close was he to the action that he was wounded by a German mortar round while with U. S. paratroopers and Rangers near Cassino and was hospitalized for five months. Among his other books was John F. Kennedy and PT-109 for the Random House Landmark Books series, which I also read as a kid.

Also writing for the Landmark Books series was Quentin Reynolds, who covered the war for Collier’s Weekly. Reynolds was a product of the Bronx. In fact, he played one season as a lineman for the NFL’s Brooklyn Lions. Reynolds was a prolific author, writing more than 30 books, many of them for the Landmark series.

Perhaps the correspondent best remembered today is Ernie Pyle, who covered the war for the Scripps-Howard newspapers. He wrote in a simple, down-home style about the ordinary soldier, naming many of those of whom he wrote and giving their home towns. He wrote of the soldiers in not only Italy and France but also the Pacific theater. He was killed by a Japanese sniper while covering the Battle of Okinawa on the island of Ie Shema.

Pyle’s columns were collected and published in four books: Ernie Pyle in England (1941), Here Is Your War (1943), Brave Men (1944), and Last Chapter (1949). I had read two of those as a kid as well. Pyle won the Pulitzer for his writings.

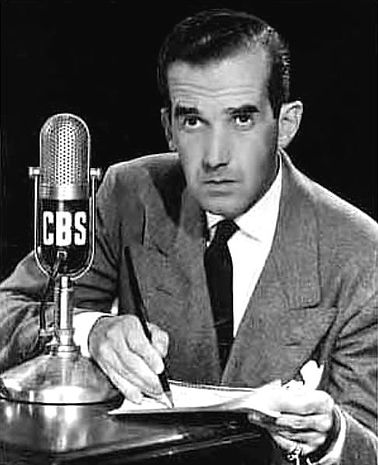

Several correspondents gained fame not so much for their published writing as for their radio reporting. Perhaps foremost in that category was Edward R. Murrow, who broadcasted from London for CBS during the Blitz. (You can hear him broadcasting during an air raid here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O7e3G2WUhD4&t=14s.)

Born in Polecat Creek near Greensboro, N.C., Murrow became the originator of the “European News Roundup” from London. He covered the 1938 Anschluss, or Germany’s annexation of Austria. He compiled his reports of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in a book titled Berlin Diary (1941). His radio broadcast was called London After Dark, during some episodes of which one could hear the air-raid sirens blaring in the background even as he broadcasted the news. He was the first reporter to broadcast about the atrocities at Buchenwald. After the war, he became director of the U.S. Information Agency, the forerunner of the Voice of America.

Another broadcaster who gained fame during the war, thereby laying the groundwork for their post-war fame, was Walter Cronkite, who reported for the United Press. He had begun as a radio announcer on WKY of Oklahoma City, using the on-air pseudonym “Walter Wilcox.” During the war, he covered the fighting in North Africa and Europe, including the Battle of Britain. He flew on bombing missions in a B-17 Flying Fortress and once even fired a machinegun at an attacking German plane. He also landed in a glider as part of the ill-fated Operation MARKET GARDEN.

After the war, Cronkite covered the Nuremberg Trials. But his voice became a mainstay of American broadcast journalism when he was the anchor of CBS Evening News. I also identify his voice as one of the narrators of the You Are There historical educational episodes.

The rose among thorns of war correspondents was without question Dorothy Thompson. Called the “First Lady of American Journalism,” she was the first American journalist expelled from Nazi Germany (1934) after she interviewed Adolf Hitler and angered him with her transparent portrayal of him and his rising Nazi regime. Her expulsion papers were delivered to her by a Gestapo agent. She later wrote a book titled I Saw Hitler.

Thompson became a foreign correspondent in 1920 for the International News Service. She also wrote for the Philadelphia Public Ledger and the New York Evening Post. She was the first woman to head a foreign news bureau. A prolific writer, she wrote a three-times-a-week column titled On the Record for the New York Herald Tribune that was syndicated in more than 170 other papers. She also wrote a monthly column for the Ladies Home Journal. In addition, she had a radio broadcast on NBC. (You can hear her voice here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vsz8DzcmhMs.) Amid all her activities, she found time to write 21 books.

These were just a few of the most famous of the scores of American war correspondents during World War II. Without their reporting and writing, our knowledge of the war, its events, and the people involved in them would be sorely lacking. It would be well worth the effort to find and read much of their writings.

Write2Ignite just posted an article based on an interview of me about my book Combat! Spiritual Lessons from Military History. You can view it at

Write2Ignite just posted an article based on an interview of me about my book Combat! Spiritual Lessons from Military History. You can view it at  I just finished reading a delightful little book that addresses, explains, and illustrates just what that corrected version of the saying means. The book is Master of One by Jordan Raynor. I wish that that book had been available to me when I was a young college student, repeatedly changing my major as I tried to figure out who I was and what God wanted me to do and who He wanted me to be. (Looking back, however, I realize that all that shifting and turning was actually a preparation for what I eventually latched onto, and that’s another point of Raynor’s book.)

I just finished reading a delightful little book that addresses, explains, and illustrates just what that corrected version of the saying means. The book is Master of One by Jordan Raynor. I wish that that book had been available to me when I was a young college student, repeatedly changing my major as I tried to figure out who I was and what God wanted me to do and who He wanted me to be. (Looking back, however, I realize that all that shifting and turning was actually a preparation for what I eventually latched onto, and that’s another point of Raynor’s book.) On any project in which we’re engaged, whether constructing a house or writing a book or pursuing a degree, it’s often good to pause to inspect our work and ensure that we’re on the right track. If we find that we’re off track, we still have time to get back on the right track and resume the work. It’s better that than to finish the job only to learn that we’ve done it all wrong but find it’s too late to do anything to correct it. This exercise is especially critical to successfully completing one’s life journey.

On any project in which we’re engaged, whether constructing a house or writing a book or pursuing a degree, it’s often good to pause to inspect our work and ensure that we’re on the right track. If we find that we’re off track, we still have time to get back on the right track and resume the work. It’s better that than to finish the job only to learn that we’ve done it all wrong but find it’s too late to do anything to correct it. This exercise is especially critical to successfully completing one’s life journey. Mathis, a photographer-musician-author, uses the analogy of a football game in focusing our attention on the preparations we are making for retirement. Just as a football game is divided into quarters, we can also envision our journey through life like that.

Mathis, a photographer-musician-author, uses the analogy of a football game in focusing our attention on the preparations we are making for retirement. Just as a football game is divided into quarters, we can also envision our journey through life like that.

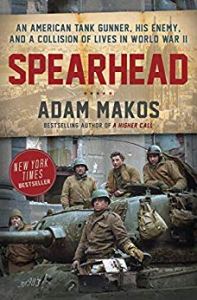

That certainly was true for me in the appreciation I’ve gained for two World War II veterans. First, it was the appreciation for my uncle’s war experiences when I followed his tank tracks during World War II. As I’ve written before in this blog, he was a tank driver for forward observers of the 391st Armored Field Artillery Battalion, 3rd Armored Division, the tip of the spear thrusting deep into Hitler’s Germany. The books Death Traps by Belton Y. Cooper and Spearhead by Adam Makos only deepened my appreciation for what Uncle Dillon went through.

That certainly was true for me in the appreciation I’ve gained for two World War II veterans. First, it was the appreciation for my uncle’s war experiences when I followed his tank tracks during World War II. As I’ve written before in this blog, he was a tank driver for forward observers of the 391st Armored Field Artillery Battalion, 3rd Armored Division, the tip of the spear thrusting deep into Hitler’s Germany. The books Death Traps by Belton Y. Cooper and Spearhead by Adam Makos only deepened my appreciation for what Uncle Dillon went through.

Perhaps the most gut-wrenching account in the book is one that Stars and Stripes correspondent Andy Rooney recounted. The belly turret of one Fortress was badly damaged by gunfire. The gunner was trapped inside. The crew worked feverishly but unsuccessfully to extract him. But I’ll let Miller and Rooney describe the rest:

Perhaps the most gut-wrenching account in the book is one that Stars and Stripes correspondent Andy Rooney recounted. The belly turret of one Fortress was badly damaged by gunfire. The gunner was trapped inside. The crew worked feverishly but unsuccessfully to extract him. But I’ll let Miller and Rooney describe the rest:

The personal connection that increased my appreciation for those young fighters in the air was my wife’s uncle, Sgt. Paul Bagosy, who was a tail gunner in one of those B-17s, a member of the 546th Bombardment Squadron, 384th Bomb Group. (He’s kneeling on the far right, front row, of the accompanying crew photo.) Because enemy fighter pilots liked to attack the bombers from behind, the tail gunner was in a vulnerable position. Many of them, including the one who manned the tail gun in the B-17 shown in the accompanying photo, didn’t make it back. Unlike many of his fellow airmen, however, Paul lived to complete the required 25 missions and returned home.

The personal connection that increased my appreciation for those young fighters in the air was my wife’s uncle, Sgt. Paul Bagosy, who was a tail gunner in one of those B-17s, a member of the 546th Bombardment Squadron, 384th Bomb Group. (He’s kneeling on the far right, front row, of the accompanying crew photo.) Because enemy fighter pilots liked to attack the bombers from behind, the tail gunner was in a vulnerable position. Many of them, including the one who manned the tail gun in the B-17 shown in the accompanying photo, didn’t make it back. Unlike many of his fellow airmen, however, Paul lived to complete the required 25 missions and returned home. I foresaw trouble as soon as I flipped through the pages of this newly arrived book I had received to review. It was Travane by M.D. Schlatter (Dot’s House, 2011).

I foresaw trouble as soon as I flipped through the pages of this newly arrived book I had received to review. It was Travane by M.D. Schlatter (Dot’s House, 2011). The novel, Autumn Frost by M.D. Schlatter, is part of her in-progress series. (The next installment is Winter Tumult. Who knows? I might read that book, too; perhaps the entire series. For me to read any fiction is an accomplishment; an entire series would be amazing.)

The novel, Autumn Frost by M.D. Schlatter, is part of her in-progress series. (The next installment is Winter Tumult. Who knows? I might read that book, too; perhaps the entire series. For me to read any fiction is an accomplishment; an entire series would be amazing.)