The key factor in determining whether one likes or dislikes history (or any subject, for that matter) is the kind of teachers he or she has. A bad teacher can easily turn a student away from the subject, but a good teacher can dispel that negative influence and instill a life-long interest in the subject.

I’ve had both kinds of teachers, thankfully more of the latter than of the former, and they had a far-reaching influence on my love of history.

I suppose the teacher who first awakened me to the enjoyment of history was Mrs. George in fifth grade. It was through her reading contest that my eyes were opened to the vast expanse of interesting books on historical subjects that lined the shelves of our small school library. The Landmark Books by Random House were just the beginning, but they were the spark that set me on fire.

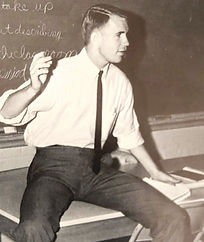

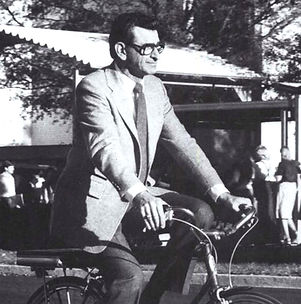

In junior high, I had two good teachers who furthered my interest in history and what was required to get the most from it. Richard Booher (left) helped me realize the importance of place (geography) to developing an understanding of history. And Frank Galbraith (right) taught me the excitement of history by acting out historic scenes in class. I can still see him (in my memory bank) rushing into the classroom and dragging a classmate from the room, calling out as they exited that he was going to make a sailor of him, all to illustrate the methods of Prince Henry the Navigator in developing a navy for Portugal and thereby initiating the Age of Discovery.

Then, in high school, Hubert Lakin epitomized the skill of mentally “seeing” history as it unfolded. He often taught sitting behind his desk (something that was anathema for one of the principals under whom I later taught). I often watched him staring out the window as he waxed quietly eloquent about some historic event, something he was “seeing” in his mind’s eye. Suddenly, he would leap excitedly from his chair and pace up and down between the rows of desks, drawing some conclusion or making some application from what he had “seen” and had been trying to get us students to see from his description.

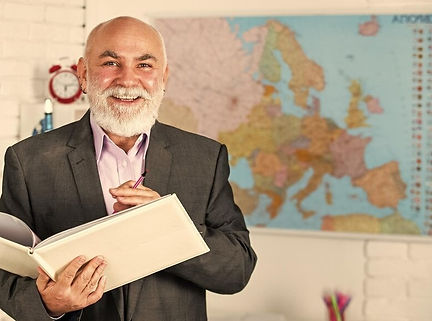

In college, I had several good history teachers, but two stood head and shoulders above the others. Dr. Edward Panosian taught History of Civilization to all freshmen, but his main teaching assignments were upper-level and graduate history courses. As a freshman, I sat mesmerized as he taught, awed by not only his vast knowledge but also his dignified manner and sonorous voice. I could hardly wait to take his upper-level courses. His much smaller senior course in Reformation history only increased my admiration for the man, and his love for his subject was contagious. So enthralled was I with his lectures that I sometimes forgot to take notes. I left the classroom mentally exhausted but inspired to imitate his electric teaching style.

I’m by no means the only one whom Panosian influenced. Among the literally hundreds of others so influenced was Asa Hutchinson, governor of Arkansas, who wrote, “I will never forget the passion of Dr. Panosian’s teaching of history and the clarity with which he taught about two different world views that have defined our past. He instilled into me a love for history and how it can inform us as we address the challenges of this generation.”

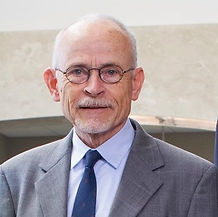

Finally, there was Dr. Carl Abrams. He spoke with a quiet, somewhat gravely voice, a stark contrast to Panosian, so I made sure to sit in the first or second row of his classes so I could hear. When I was unable to fit his class on the History of the South into my schedule because of my work schedule and the fact that the course was offered only every three or four years, he worked out a deal with the dean so I could take it.

I would meet him in his office after work once every two weeks, and he would teach me one-on-one. He gave me a long list of book titles related to Southern history on which he had highlighted ten titles that he dictated were required reading. I was to choose an additional ten titles and read two books and write a paper on one of the two books every two weeks and then meet him in his office to discuss them. At the end of the course, he gave me profound advice that I’ve employed in researching my own writing projects: Whenever you read a book, study the author’s bibliography and read many of the books listed there. As a token of my thanks and appreciation, I presented him a copy of my first published book, Confederate Cabinet Departments and Secretaries, for which he had been a great encouragement.

Following his advice, I will certainly never run out of books to read! More importantly, I’ll learn more and have a vast storehouse of source material for my own future writing on historical topics.

Those are the teachers who fired my interest in history. What about you? Which teachers have influenced your own favorite subject and how? Please share in the comments.

Examples of this phenomenon abound all around us. This is no reflection on the utility or value of the products or services of such companies. It’s no reflection on the creative ingenuity of the firms’ marketing gurus. But it is a reflection of why otherwise educated kids grow into adults who can’t spell or write correctly. With so many bad examples surrounding them, the wonder is that they can spell and write as well as they do!

Examples of this phenomenon abound all around us. This is no reflection on the utility or value of the products or services of such companies. It’s no reflection on the creative ingenuity of the firms’ marketing gurus. But it is a reflection of why otherwise educated kids grow into adults who can’t spell or write correctly. With so many bad examples surrounding them, the wonder is that they can spell and write as well as they do! I think back to my mother’s handwriting. Neat. Legible. Even artistic. Even when she was scribbling her grocery list in a hurry, her handwriting was still clearly legible. Certainly better than mine when I took my time. And that seems to have been a characteristic of her entire generation, at least for the women but also for many of the men. And the key is that they were TAUGHT to practice good handwriting! It didn’t just happen. Typically, it was either the Palmer or the Zaner-Bloser technique they learned. And it stayed with them. Distinctive, artistic, and legible to the very end!

I think back to my mother’s handwriting. Neat. Legible. Even artistic. Even when she was scribbling her grocery list in a hurry, her handwriting was still clearly legible. Certainly better than mine when I took my time. And that seems to have been a characteristic of her entire generation, at least for the women but also for many of the men. And the key is that they were TAUGHT to practice good handwriting! It didn’t just happen. Typically, it was either the Palmer or the Zaner-Bloser technique they learned. And it stayed with them. Distinctive, artistic, and legible to the very end! A rule of education is that you will get from students what you reward. If you reward a particular behavior, it gets repeated. If you pay attention to the guy who’s goofing off just to get attention, he’ll keep doing it. If you honor and reward good spelling and handwriting, students will soon pick up on that and begin to spell and write well.

A rule of education is that you will get from students what you reward. If you reward a particular behavior, it gets repeated. If you pay attention to the guy who’s goofing off just to get attention, he’ll keep doing it. If you honor and reward good spelling and handwriting, students will soon pick up on that and begin to spell and write well. When was the last time you wrote a thank-you note or letter? By hand? How is your own spelling? We must set the example. People will know we’ve taken the time and made the effort to express our thoughts. At least they’ll be able to read them! Moreover, something handwritten is something that might actually be cherished and saved. That text message or e-mail will soon be deleted and forgotten.

When was the last time you wrote a thank-you note or letter? By hand? How is your own spelling? We must set the example. People will know we’ve taken the time and made the effort to express our thoughts. At least they’ll be able to read them! Moreover, something handwritten is something that might actually be cherished and saved. That text message or e-mail will soon be deleted and forgotten. As the school bus topped the hill at my grandfather’s driveway and headed toward its next stop, the end of our driveway, I panicked and began crying and drawing back toward the house. Mother guided (more accurately, she pushed) me toward the bus stop. I cried harder and pulled her back toward the house. I suddenly didn’t want to go to school after all!

As the school bus topped the hill at my grandfather’s driveway and headed toward its next stop, the end of our driveway, I panicked and began crying and drawing back toward the house. Mother guided (more accurately, she pushed) me toward the bus stop. I cried harder and pulled her back toward the house. I suddenly didn’t want to go to school after all! After that, however, I had no problem with going to school. I actually looked forward to it. Although to admit any joy of learning was never considered wise among peers, I relished learning and still do.

After that, however, I had no problem with going to school. I actually looked forward to it. Although to admit any joy of learning was never considered wise among peers, I relished learning and still do. When my brother, sister, and I were growing up, our parents taught us more by their example than by their spoken instruction, although they did a lot of that kind of teaching, too.

When my brother, sister, and I were growing up, our parents taught us more by their example than by their spoken instruction, although they did a lot of that kind of teaching, too. Our parents were children of the Great Depression. They knew firsthand what tough economic times were. They had learned the hard way how to make it last, wear it out, make do, and do without. To do that, they had learned what was necessary in life, to control or suppress the urge for instant gratification, and to save for both the proverbial rainy day and the truly important things that they hoped one day to have or to give to us.

Our parents were children of the Great Depression. They knew firsthand what tough economic times were. They had learned the hard way how to make it last, wear it out, make do, and do without. To do that, they had learned what was necessary in life, to control or suppress the urge for instant gratification, and to save for both the proverbial rainy day and the truly important things that they hoped one day to have or to give to us. We learned almost from the time we learned to verbalize a simple sentence that it was a bad idea to interrupt an adult conversation. We learned to wait until the conversation was over or the people having the conversation paused before speaking. As we got older, we learned that to interrupt someone is downright rude, the epitome of selfishness. It is a way of saying, “I’m more important than you” or “What I’ve got to say is more important than what you are saying.”

We learned almost from the time we learned to verbalize a simple sentence that it was a bad idea to interrupt an adult conversation. We learned to wait until the conversation was over or the people having the conversation paused before speaking. As we got older, we learned that to interrupt someone is downright rude, the epitome of selfishness. It is a way of saying, “I’m more important than you” or “What I’ve got to say is more important than what you are saying.” This saying we usually heard just before we left our parents to go somewhere without them. It was a reminder to be on our best behavior and to do right, regardless of what others around us might do. They wanted us to realize that what we said and did and the behavior decisions we made reflected on not only our own character but also the entire family and had potential consequences for every member of the family. It was a reminder to do our family proud by being and doing right at all times.

This saying we usually heard just before we left our parents to go somewhere without them. It was a reminder to be on our best behavior and to do right, regardless of what others around us might do. They wanted us to realize that what we said and did and the behavior decisions we made reflected on not only our own character but also the entire family and had potential consequences for every member of the family. It was a reminder to do our family proud by being and doing right at all times. One of the writers who has been most helpful to my own writing is William Zinsser. Although he was an accomplished journalist and freelance writer, undoubtedly his most influential work was the first book of his that I ever read, On Writing Well.

One of the writers who has been most helpful to my own writing is William Zinsser. Although he was an accomplished journalist and freelance writer, undoubtedly his most influential work was the first book of his that I ever read, On Writing Well. I just recently completed another of his books, Writing About Your Life: A Journey into the Past. In it, he offers some down-to-earth and practical advice for writers of memoir. What better way to remember him than by considering what he had to say to those of us who are, or who want to become, writers?

I just recently completed another of his books, Writing About Your Life: A Journey into the Past. In it, he offers some down-to-earth and practical advice for writers of memoir. What better way to remember him than by considering what he had to say to those of us who are, or who want to become, writers? Years ago, perhaps sometime in the early Seventies, I read an article in the Knoxville News-Sentinel by famed war correspondent and syndicated columnist Don Whitehead titled “On Where Time Goes.” In that article, he ruminated about what he had done over the years of his life, how he had filled his allotted time on this earth.

Years ago, perhaps sometime in the early Seventies, I read an article in the Knoxville News-Sentinel by famed war correspondent and syndicated columnist Don Whitehead titled “On Where Time Goes.” In that article, he ruminated about what he had done over the years of his life, how he had filled his allotted time on this earth. I’ve had that question go through my mind before as I’ve watched my grandchildren at play. I’ve found myself seeing in them my own daughters, and I’ve nudged my wife and whispered, “Look at that! Doesn’t that remind you of” [and I’ve named one of our daughters] “when she was that age?”

I’ve had that question go through my mind before as I’ve watched my grandchildren at play. I’ve found myself seeing in them my own daughters, and I’ve nudged my wife and whispered, “Look at that! Doesn’t that remind you of” [and I’ve named one of our daughters] “when she was that age?” The transmission of knowledge from one generation to the next, Sun Tzu taught, was the key to long-term military success. . . . [The Bible] enjoined parents to teach their children at every possible opportunity . . . and pastors were to teach their congregations. . . .

The transmission of knowledge from one generation to the next, Sun Tzu taught, was the key to long-term military success. . . . [The Bible] enjoined parents to teach their children at every possible opportunity . . . and pastors were to teach their congregations. . . . We must contend for the truth in the small things. If we don’t contend for small things, we’ll never contend for big things. . . . Faithfulness in that which is least shows qualification for being in charge of that which is great (Matthew 25:21, 23).

We must contend for the truth in the small things. If we don’t contend for small things, we’ll never contend for big things. . . . Faithfulness in that which is least shows qualification for being in charge of that which is great (Matthew 25:21, 23). Mark Twain famously wrote, “The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.”

Mark Twain famously wrote, “The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.” For example, people flippantly describe politicians’ actions as “Nazi” or “fascist” when neither the people being so described nor their actions remotely resemble those totalitarian positions. The terms are now merely emotion-laden buzz words that garner knee-jerk emotional responses among equally uninformed hearers or readers. Those who use such terms so glibly are either clueless as to their true meanings or purposely deceptive in their word choice.

For example, people flippantly describe politicians’ actions as “Nazi” or “fascist” when neither the people being so described nor their actions remotely resemble those totalitarian positions. The terms are now merely emotion-laden buzz words that garner knee-jerk emotional responses among equally uninformed hearers or readers. Those who use such terms so glibly are either clueless as to their true meanings or purposely deceptive in their word choice. One characteristic of an advanced civilization is its possession of a precise language system. Conversely, one sign of a degenerating society is its misuse of its language. The consequences of a degenerating language are potentially far greater than the difference between the words in Twain’s lightning and lightning bug analogy.

One characteristic of an advanced civilization is its possession of a precise language system. Conversely, one sign of a degenerating society is its misuse of its language. The consequences of a degenerating language are potentially far greater than the difference between the words in Twain’s lightning and lightning bug analogy.